VIEWS: 9652

August 31, 2022Taté Walker Talks ‘The Trickster Riots’ and Collaborating With Family

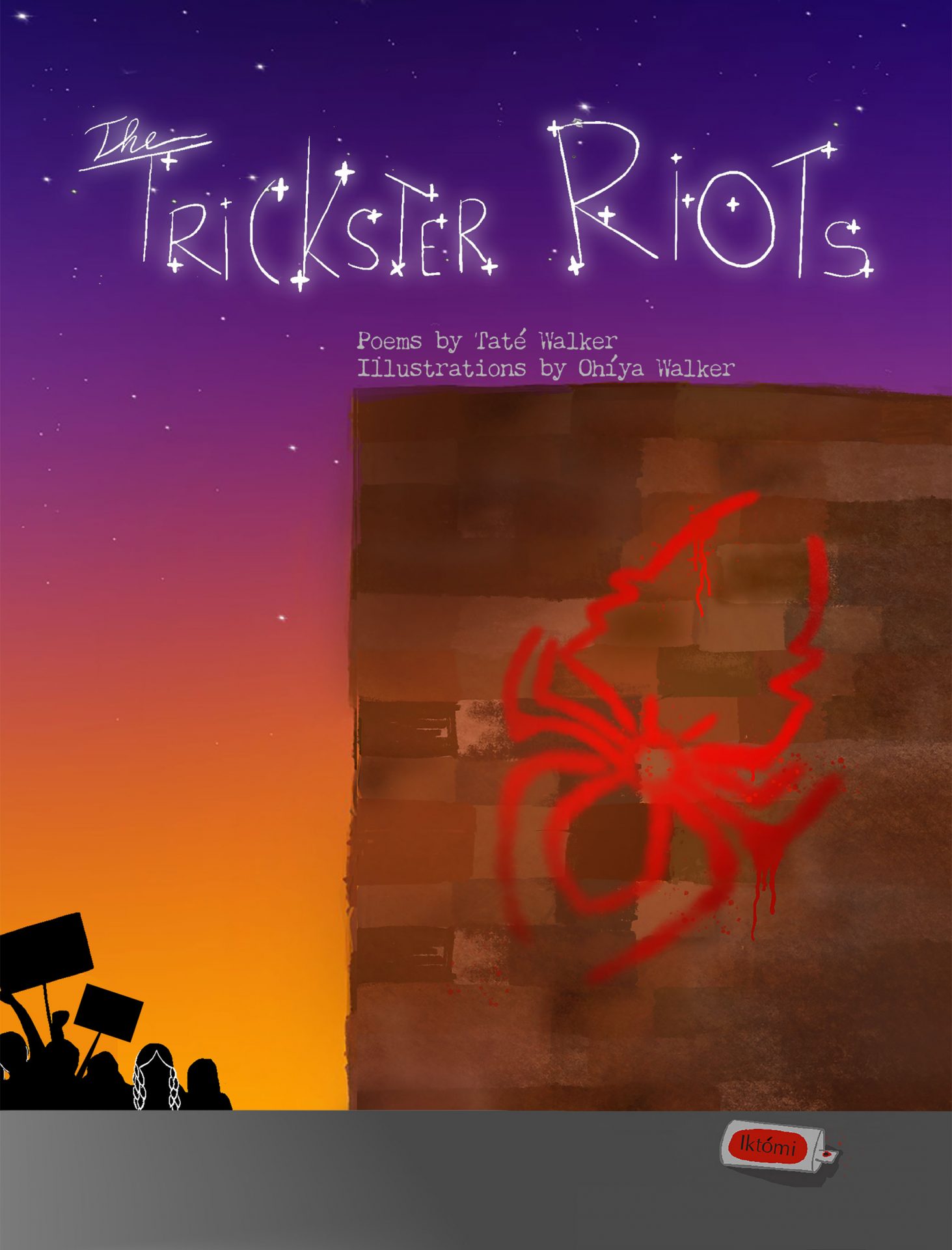

Salt River Schools Communications and Public Affairs Director Taté Walker (Lakota citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe of South Dakota) has released a new poetry collection called “The Trickster Riots” with illustrations by their 14-year-old child, painter and graphic artist Ohíya Walker (Lakota citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe/Red Lake Ojibwe/Mvskoke Creek).

For those who don’t know, besides working in the Community in their role at Salt River Schools, Walker is an award-winning Two Spirit storyteller who has been a professional journalist for newspapers and print and online magazines for nearly 20 years.

“Being Two Spirit and being a storyteller are one in the same. They are inseparable. Through a lot of deep, ceremonial work with Lakota elders, relatives and community, I was recognized as Winyan Witko, which has its own literal translation but boils down to ‘Two Spirit,’” said Walker. “My relations recognized that I had medicine to share directly tied to storytelling (journalism) and the experiences and perspectives I have being queer.”

With the release of “The Trickster Riots,” Walker has been traveling throughout the Valley and the U.S. to perform, in a slam-poetry style, the works about Iktómi, the Lakota trickster, who takes shape as a spider.

“I try to read like I’m telling you the best edge-of-your-seat story ever. There’s a lot of arm movements, winks and fast pacing. I think audiences respond well to that,” said Walker.

Walker had been researching tricksters like Iktómi for a book they were writing and several themes came up that inspired most of the poems: disruption, anti-authority, queerness and out-of-the box thinking.

“The trickster gets caught up in some ridiculous, humiliating and downright terrible situations—you don’t want to be like Iktómi,” said Walker. “But as I researched the stories as they were told in my Lakota language, it became clear that something was being lost in translation. Across the board, I was finding that when told in their traditional languages, tricksters weren’t good or bad. They have purpose and power.”

As for working with family on a creative project, Walker said both grew closer as mother and child through the many conversations they had about the poem topics and their creative differences.

“A big credit goes to my publisher for being willing to experiment with poetry in this way. Ohíya is so talented, and the way they interpreted my poems influenced how I revised a lot of my flow and word choices,” said Walker.

Ohíya’s influences can be linked back to their Lakota and Ojibwe ancestors.

“I love to combine traditional art forms and patterns with my own contemporary style,” Ohíya said. “I am constantly drawing or painting Ojibwe floral patterns and Lakota geometric designs on whatever surfaces are around me, including digital spaces.”

Walker just finished the first draft of a children’s book and will be performing their poetry at the South Dakota Festival of Books in late September and at the Salt River Tribal Library in December. To learn more about their work, you can visit www.jtatewalker.com.