VIEWS: 3099

March 18, 2023Traditional Form of O’odham Calendar Explored

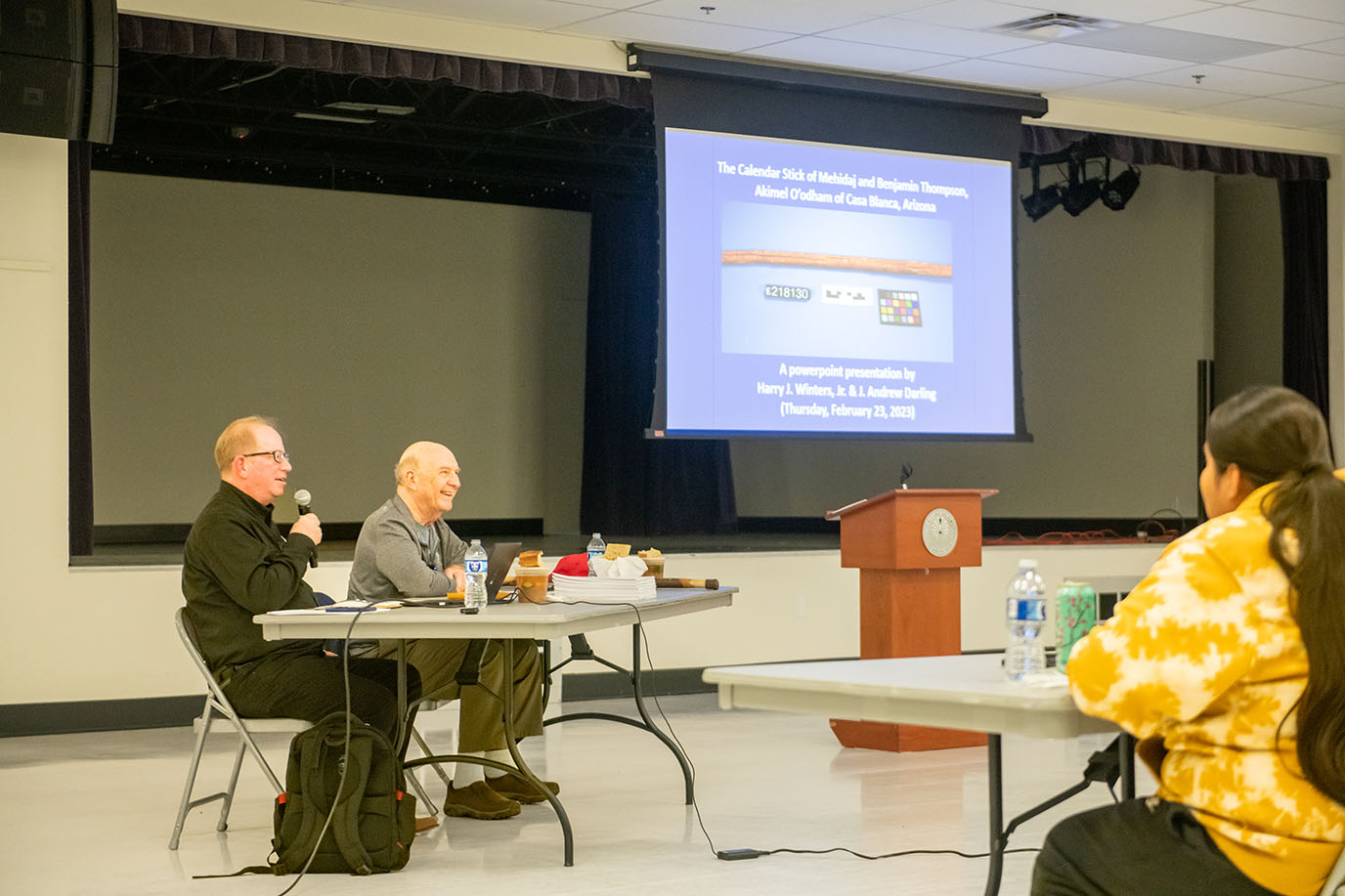

On February 23, Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community members came out to Community Building to learn about calendar sticks. The SRPMIC Cultural Resources Department invited scholars Harry J. Winters Jr. and J. Andrew Darling to give a presentation on traditional Akimel O’odham and Tohono O’odham calendar sticks and how these artifacts record the history of the people.

The presentation centered on the Calendar Stick of Mehidaj and Benjamin Thompson, from District 5 (Casa Blanca) on the Gila River Indian Community. This calendar stick, which is housed in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, holds important dates in O’odham history. Winters and Darling wrote a research article about this calendar stick that was published in the Spring 2022 issue of the Journal of the Southwest, published by the University of Arizona.

Recording History

The O’odham from the Gila River Indian Community, the Tohono O’odham Nation, and the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community used calendar sticks to record the story of the people. The sticks were 35 to 55 inches long and inscribed with notches and symbols to denote years and notable events of history in the region. They could be made from a willow branch, a pine branch or saguaro cactus ribs.

According to Winters and Darling, calendar sticks followed the O’odham new year, which begins in July and ends the following June. Each new notch signified a new year, and there were 1 to 2 inches of spacing between each notch where figures, dots, designs, colors and shapes would be made by the stick holder relating to their observations and memories of tribal events that year. Eventually, the one who made the stick would be able to recite important events in tribal history from memory.

The calendar stick would be passed down to a male member of the family, who would carry on the role of inscribing events on the stick. If the calendar stick could not be passed to a male relative, it would be destroyed (most likely broken into pieces) and then buried with the deceased owner. Darling said that according to a report by anthropologist Dr. Frank Russell on the Pima Indians for the Bureau of American Ethnology, published posthumously in 1908 (Russell died in 1903), one calendar stick belonging to a stick holder was lost, so he resorted to recording the tribe’s stories with pencil and paper. Russell was an anthropologist and ethnologist working among the Akimel O’odham of the Gila River Indian Community from 1901 to 1903, and he documented the Calendar Stick of Mehidaj and Benjamin Thompson.

In particular, the Calendar Stick of Mehidaj and Benjamin Thompson is significant because it documents events ranging from about 1842 to 1892. Little is known about Mehidaj, who is briefly described in small notations in one of Russell’s typescripts that mentions the name Mehidaj (meaning “burnt remains”—of something or someone).

According to Russell’s typescript, Mehidaj passed his calendar stick on to Benjamin Thompson, who continued to document events, such as skirmishes and battles with Apache and Yavapai raiders, tribes who were frequently at odds with the O’odham. Mehidaj may have possessed the calendar stick for 59 years, and Thompson had the stick for 14 years prior to meeting Russell.

Throughout Russell’s 1901-1902 fieldwork in central Arizona as an employee of the Bureau of American Ethnology, at least four calendar sticks were studied, translated and documented. These calendar sticks were made by Juan Thomas of Blackwater (District 1), Benjamin Thomas of Casa Blanca (District 5), and Joseph Head (Ko’oi Mo’o—Rattlesnake Head) and Chukud Naak (Owl Ear), both from Gila Crossing (District 6). It was noted that Owl Ear would later move to the SRPMIC.

Of the three calendar sticks, the Casa Blanca stick is the only original, while the two others that are from GRIC are copies, currently in the Smithsonian collection, while the Chukud Naak stick is in the collection of the Arizona Museum of Natural History, according to Darling and Winters. Later, in 1920, the original Gila Crossing stick came into the possession of an Edward Davis, a “collector” of artifacts, and it later found its way to the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C.

Place names associated with the Benjamin Thompson calendar stick include Chuchk Daadk (Black Noses), an area near the Rillito cement plant between Tucson and Marana. The O’odham name describes several low-lying hills from the Tucson Mountains that are a dark earthen color.

Throughout the presentation, Darling and Winters provided an overview of several events marked on the Thompson calendar stick. The range of history it documents geographically records a footprint that extends from east of Miami, Arizona (near Globe) to Queen Creek, Tucson, Cave Creek and the Verde River.

In one recorded event, Apache ambushed the O’odham near Chuchk Daadk. The O’odham would refer to the Apache as oob (enemy). The name oob is a common word associated with both the Apache and Yavapai and appears in historical accounts to describe the parties involved.

Another incident documents the capturing of an Apache cattle thief at the hands of the Akimel O’odham on the Gila River Indian Community around 1845 to 1846. Later, the captured Apache would be dispatched by women with sticks, after a period of dancing and singing connected to the series of events.

The encounter took place in an area between District 4 (Gila Butte) and District 5 (Casa Blanca) called Aji Mountain. Westbound travelers on Interstate 10 can see the mountain to their right, which is divided into two buttes called Bibjulik and Aji, situated in a north to south direction.

Russell describes another translated account from the calendar stick in the Mazatzal and Superstition Mountains. This area was a territory associated with the Apache and bands of Yavapais, along with the O’odham.

Around 1860 to 1861, O’odham and their white compatriots fought a group of Apaches, which resulted in two mortally wounded O’odham warriors and an unknown count on the Apache side. In Russell’s later translations, the Four Peaks area was the site of many battles relating to either the Apache or Yavapai tribes.

Darling and Winters did their best to describe the stories and places associated with the calendar stick and how they are associated with present-day GRIC, SRPMIC, the Tohono O’odham Nation, and the Yavapai and Apache people. Some stories also involve the western edge of O’odham territory, dealing with the Piiapaash (Maricopa) and Yuman tribes.