VIEWS: 2281

October 3, 2024Sharon Selestewa and Patsy King Bond Over Language in Latest O’odham Class Series

Editor’s Note: This story contains sensitive subject matter, including memories of childhood punishment that some readers may find triggering.

When Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community member Patricia “Patsy” King was approached to instruct a language class series at the Salt River Tribal Library along with fellow Community member Sharon Selestewa, she was so excited about the opportunity that she exclaimed, “Well, I want to do that with her!”

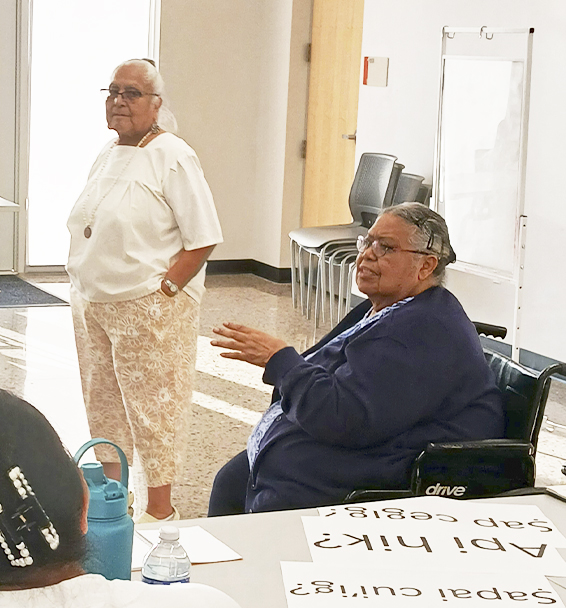

The two took turns leading a three-day O’odham language gathering facilitated by the Salt River Tribal Library and Leisure Education Program at the Way of Life Facility from 6 to 7:30 p.m. on August 20, September 3 and September 10.

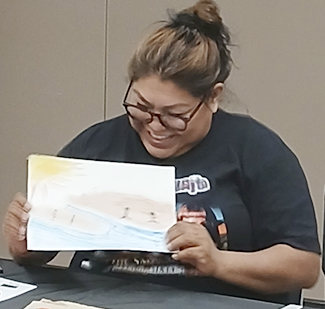

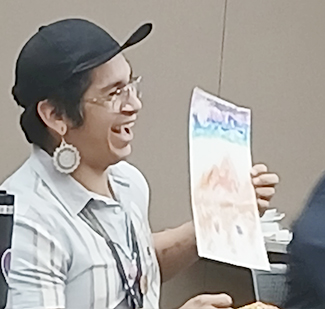

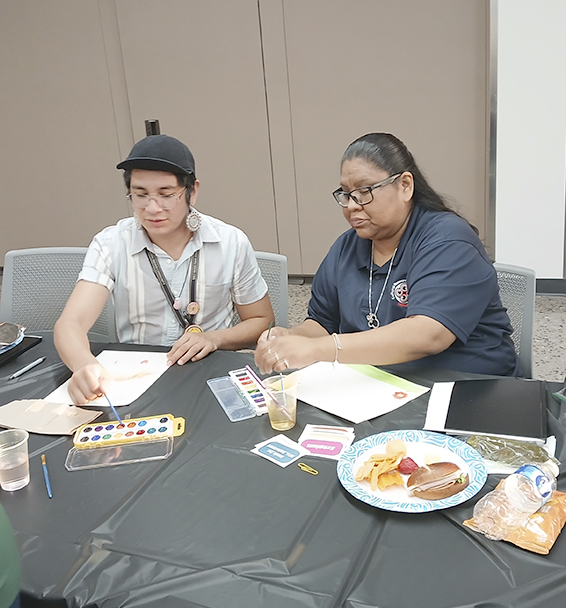

Twelve enrolled SRPMIC members signed up for the at-capacity class, where they learned O’odham vocabulary for numbers and colors from Selestewa and words associated with eating and utensils from King, among other topics. Selestewa’s daughter Tammy “Tamale” Walker and her daughter Kasheen Walker also assisted with the language gathering.

King views Selestewa as a master O’odham Ñiok (“language” in O’odham) teacher, and Selestewa feels just as fondly about King.

While Selestewa taught the O’odham Ñiok before King did, both women grew up with O’odham as their first language. The language was instilled in them before and right after they were born—something that King says is happening less often these days. It’s one of the motivating factors for her to continue offering her wisdom to people who want to learn or reconnect with the language.

“I was born at home,” said King, whose mother told her that her grandmother on her father’s side brought her into the world. “It wasn’t at a hospital. And at that time, relatives all lived around each other. So, you just had a lot of people around you all the time talking to you or talking around you, or talking about this or that [in O’odham].”

King previously worked at Salt River Schools’ Early Childhood Education Center, which incorporates the O’odham language into the curriculum at an early age. King’s vision also involves teaching more adult speakers, who can bring the language into their homes and at family gatherings.

She recalls walking around her neighborhood as a child and stopping at the homes of family members, hearing O’odham spoken in each place. King would often see Selestewa with the James family, a family that bonds King and Selestewa together as relatives. King’s grandmother, who is Selestewa’s aunt, is a James.

“I would go across the field to visit my cousin Sharon and play there, but everybody would be talking in O’odham,” she said, as she noted that the kids would be speaking in O’odham too. “I would go over to Sharon’s mom’s house, and she would feed us lunch. She’d ask us in O’odham if we were hungry and tell us to himk daiwan (‘go sit down’ in O’odham) and she would make something for us.”

Selestewa and King coming together to continue these language traditions is full circle for the two lifelong O’odham speakers, who both have an exciting and fun approach to teaching the language.

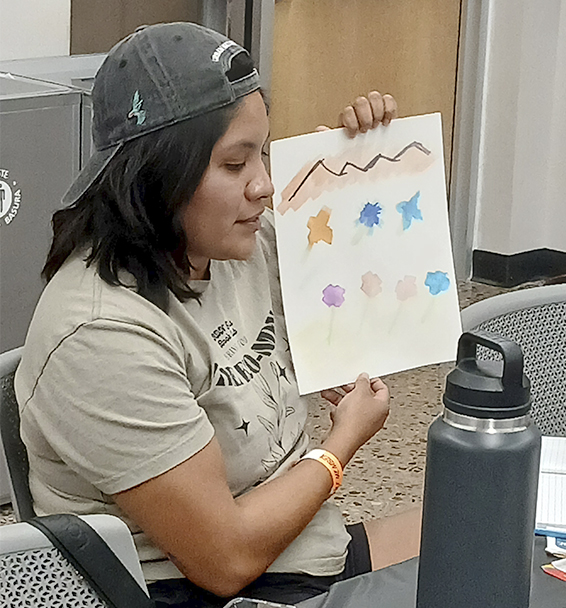

From learning to write O’odham words how they sound rather than how they’re spelled, to painting a picture with the colors they learned in the session, the participants were engaged, according to Selestewa.

Before this language series, it had been some time since Selestewa had taught the language, especially to children, citing her health and inability to get up and down. So, the chance to teach the language again on her own terms—with the help that she needs—was the perfect situation for her.

“Just being in the classroom again and teaching, I look forward to it,” said Selestewa.

Selestewa was raised by her grandparents in an O’odham-speaking household. “I didn’t know any English,” she said.

Selestewa thought back to when she was at the age to take a beginner’s English class. She remembered when she was punished for speaking O’odham on a couple of occasions.

“[Teachers] heard me outside of class [speaking O’odham] and made me stick soap in my mouth and stand in the girls’ bathroom in the corner for I don’t know how long. It seemed like hours,” she said.

“And then in the classroom, when the teacher heard me say something to a student in the O’odham Ñiok, she hit me with the ruler on my knuckles.”

Selestewa said she would go home and cry to her grandfather, and her grandfather told her that this means that she had to s’hottam (“hurry or hurry up” in O’odham) and learn the language so she wouldn’t keep getting punished.

“Crying is not going to help you,” her grandfather said at the time.

So, Selestewa quickly learned English so she wouldn’t have to endure punishments like other kids. She said they “got it worse,” being hit with paddles; it was mostly male students, from what she observed.

King attended a Bureau of Indian Affairs school, where she was also forbidden to use the O’odham language.

“I was told, ‘You’re an American now,’” said King. “You’re not a heathen. You’re not ‘this’ or ‘that’—whatever they wanted to call us. And so we would be punished.” King wasn’t physically punished, but she was reprimanded or set aside for speaking O’odham.

Both King and Selestewa wished they had taught the language more thoroughly in their own homes to their children when they were being raised, but making up for lost time is what drives them to continue to teach the language today, in their own way.

Selestewa is thankful that she grew up in a time when she could speak her language, which gives her pride in teaching it to others now.

“It’s so much fun talking in your own language, especially when you’ve run into somebody that speaks O’odham,” said Selestewa. “Then we start to converse, and it really brings back old times. Old times of going hunting for jackrabbits and doves, and cicadas in the mesquite trees nearby. They [the cicadas] tasted like chargrilled steak!”