VIEWS: 5937

August 5, 2020Baidaj Harvesting

Summer is an important season for the O’odham and Piipaash. It marks the beginning of the new year and a time to celebrate a fruitful harvest and the rain that comes in the summer. The baidaj, or harvesting of saguaro fruit, is an important ritual of the summer. When this fruit is ripe, the O’odham and Piipaash people go out into the desert to harvest it.

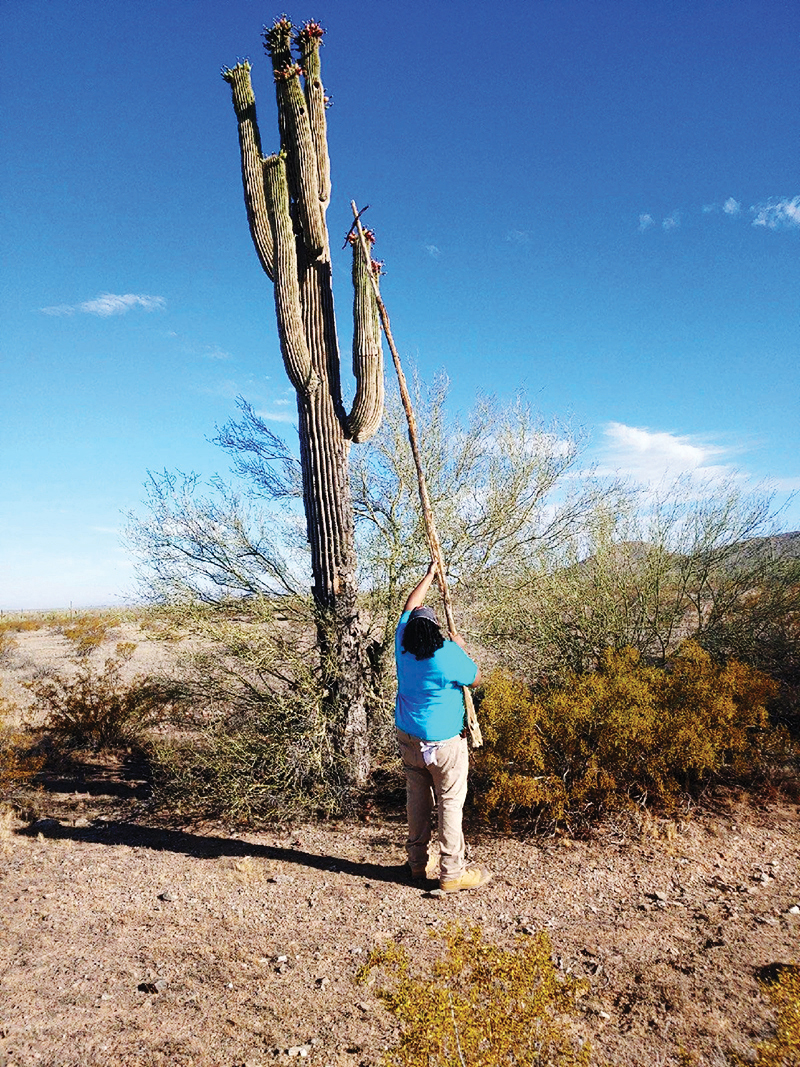

There are many cultural reasons why the fruit is harvested; primarily it is a time to come together and to help each other with picking the fruit. It all starts with a tool called the kuipad, which is created from long saguaro cactus ribs tied together using wire. Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community member Ron Carlos explained how the tool is used to knock the fruit off the top of the saguaro cactuses.

“We made a couple kuipad out of saguaro cactus ribs,” Carlos said. “I tied the cactus wood together with baling wire. A small crossbar is put on one end of the pole; that is the part used to knock off the fruit.”

For Tohono O’odham Nation member Andrew Pedro, the baidaj starts a little bit before the fruit is ripe.

“To me, the process actually starts earlier,” Pedro said. “Watching where the hasan starts to bloom and where the bahidaj is growing. Gather vapai and shegoi to make kuiput. Then harvest when [the saguaro fruits] turn red or start opening.”

Pedro must scope out where he will get the cactus ribs before he sets out to harvest.

“I look for vapai that’s already long, so I don’t have to tie that many together to get a good size,” Pedro said. “Also, [I look for] ones that are thicker in diameter so they’re stronger. And don’t bend as much as using ones that are thin. They are a bit heavier to carry around, but, in my experience, it makes for easier picking.”

Once the kuipad is created, people head out and gather the baidaj. This season, Pedro went out a few times.

“Well this season I went out, I believe, five times in about two and a half weeks,” Pedro said. “Most times from about 5 to 10 a.m., depending on what I plan to do with jun afterwards. When the bahidaj opens up and the jun is exposed, it dries and becomes really sweet. You can find the dried jun on the ground or sometimes in trees that grow close to hasan; [the fruit] falls [from the saguaro] and gets caught in branches. Or [if they’re] picked when the pods still have the jun in them, they can be left out to further dry.”

When picking the jun, a lot of harvesters take the meat and leave the pod face up to bring the rain. Some harvesters go out and pick the fruit to have a sweet snack, and others gather it to create jams and syrups to store for a later date, the most common being the sitol that can be used to spread on bread or glaze on meat. You can also make fresh juice or make a pastry with the seeds.

Gila River Indian Community member Antonio “Gohk” Davis provided some insight on the meaning behind the saguaro fruit harvest and why he goes out.

“Just really having that connection and making it yours,” Davis said. “Having it be your own family tradition, something we can carry on. Because it does make the Creator happy … [T]he way I look at it, all those hasan, they’re hundreds of years old. … [I]f hasan could talk, they have seen a lot of development. They’ve seen the good and the bad that came through our communities. They’re our elders; they are living beings. They are like our elders in our communities. They like to have those conversations, they like company. They like to invite you in, give you coffee, have a pastry, eat or just be in great company. Same thing with these hasan is to be in good company with them and pick them and let them know that you are still there. You still do care. Pick the jun, but leave the pod there. Also give thanks: Sing to them, talk to them, say a prayer for all of them because they are out there.”

Davis encourages everyone to try the harvesting process. There will be trial and error, but the only way to learn is to get your hands dirty.

“Do it with the utmost respect in your heart and your mind. Know what you will use [the fruit] for; don’t be stingy,” Davis said. “Share. It’s okay to share, especially with the Community elders who may not get out there to harvest but they know about these things. It brings back food memories and it allows them to connect with the earth again. It’s going to engage different stories and life lessons … [p]ainting a part of their life they can share with you.”